After decades of exploiting consumers, oil companies abandon renewables - good riddance?

The sad fact is that the way the oil companies make their money means that they can make much more profit out of consumers by oil and gas drilling compared to renewables

The oil companes have recently been scaling down their investments in renewable energy - such as they were. This allows them to focus on their prime goal - soaking the consumer for massive profits. This is something they have done for many decades - at a world rate of over $1600 billion a year on average so far this century.

In recent months Total, BP, Shell, BP, Chevron and Equinor have all cut their investments in renewables. Exxon, the other major western based oil company has never invested much money in wind and solar anyway. This is against a backdrop of record investments in renewables according to the IEA (see HERE). In 2024 renewables, mostly solar and wind, provided 93 per of new electricity generating capacity in 2024 (see HERE). It is not as if oil companies ever spent that much on renewables - spending on renewables amounted to a mere 4 per cent of investments in 2023 (see HERE).

I am not saying that oil company excutives are recruited on the basis of immorality. Rather it is the way that oil and gas company investments are structured that is the problem. Put simply the oil business runs on making massive profits very quickly. Any major deviation from this is likely to lead to oil company executives receiving severance pay.

The renewables industry, by and large, is predicated on modest profit levels made over long periods. Renewable energy is usually funded mostly by bank loans which have relatively low interest rates. On the other hand oil companies make big use of ‘‘equity’ - shareholders’ money - for which shareholders demand high returns.

Oil and gas company shareholders want big, sustained profits. The excuse is that oil drilling is regarded as a ‘risky’ business needing ‘equity’ ie shareholders capital, rather than bank loans. Banks will limit the proportion of total project finance that they will agree to fund through their loans. But on average the oil drilling projects make loads of money. So their projects make more money than renewable energy usually produce.

The oil companies exploit consumers

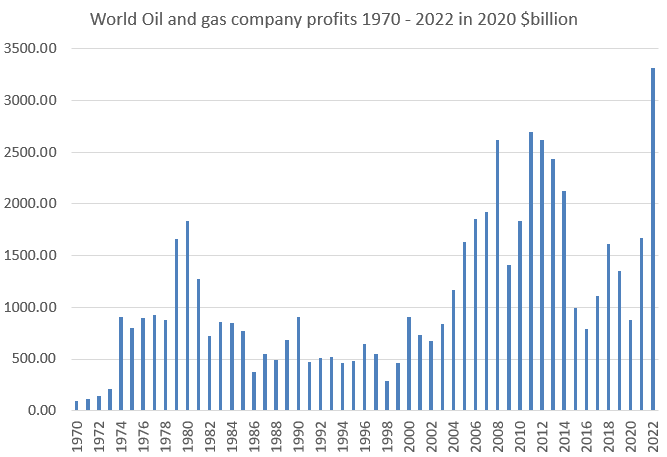

As can be seen from Chart 1, it is not just in 2002-23 that the world’s energy consumers have been soaked by oil and gas. It has been the same thing, year in, year out since oil companies existed. But oil companies thrive especially during fossil fuel energy crises.

Chart 1 World Oil and gas company profits 1970 - 2022 in 2020 $billion

Source: Verbruggen Aviel, The geopolitics of trillion US$ oil & gas rents, International Journal of Sustainable Energy Planning and Management, Vol 36 (2022), pp. 3-10, 10.54337/ijsepm.7395 ; note 2021 and 2022 profit figures are added; they were sent to me from Aviel Verbruggen (sources in turn from the IEA), which I have deflated to 2020 prices using an inflation calculatorThere were spikes in oil and later gas prices from 1973-85, from 2004 until 2014 and then the Ukraine War in 2022-3. These periods maximised oil and gas profits, as can be seen from the Figure 1. The paper from which this chart is taken includes a discussion about how geopolitical factors have produced scarcity in oil resources. This scarcity has led to prices (and thus oil company profits) being much higher than they would otherwise have been. Such geopolitical forces include the actions of OPEC in trying to ration supplies at various times, and sanctions on oil producing nations said to be hostile (to western interests) such as Iran, Venezuela, Libya and most recently Russia.

Vergbruggen concludes: ‘Since 1973, oil & gas rents (super-profits obtained without effort) have been an important objective of the major supply-side players in the business, the oil & gas exporting nations and the multinational companies like Exxon, Chevron, BP, Shell, Total, and more’. Since the year 2000 profits have average around $1600 billion a year in 2020 prices. This average profit rate is nearly 50 per cent higher than the GDP of The Netherlands, and approaches the GDP of Mexico.

The oil and gas companies have a knack of avoiding the sort of taxes that other companies have to pay. As can be seen in Figure 2 (prepared by Karl Matikonis) the tax take from oil company revenues from UK waters is very low indeed. Matikonis comments:

‘Historically, tax collections from oil and gas producers look quite low compared to their revenues………This is primarily because of generous allowances and reliefs from the UK government. The tax regime for oil and gas production differs from standard corporate taxation in the UK. Companies are liable to higher tax rates and it is “ring-fenced”. This means the extraction of gas and oil is isolated from most of the energy company’s other activities.’ (see HERE)

Figure 2 Tax collected versus revenues from oil and gas extraction in the UK

Source: Karl Matikonis, The Conversation, ‘Why energy companies are making so much profit despite UK windfall taxes’, February 8th, 2023, See HERE Why oil companies investment strategies do not suit renewables

As argued in the beginning of this blog post oil and gas companies will usually make more money out of the consumer from oil and gas investments compared to renewable energy. That is about the nature of oil and gas investments and returns compared to the (state) regulated returns that renewable investments are allowed to make. I apologise here, but it is necessary to go into some detail to explain this point!

Debt and equity investing

Oil and gas companes will use high proportions of ‘equity’ - effectively shareholders money - in the investment portfolios for oil drilling projects. This is compared to most major reneweable energy developments. According to a survey by Wind Europe ‘For onshore wind farms using project finance, the debt/equity ratio was 89:11. For offshore wind it was 78:22’, (see HERE, report page 8).

This means that wind investments will be mostly financed by bank loans. In Europe this is made possible because of secure Government-backed contracts such as ‘contracts for difference’ (CfDs) which give guaranteed fixed rate payments for energy that is generated. Bank loans carry much lower rates of return (interest charges) compared to equity investments. So wind and solar farm projects financed through CfDs will make lower profits for the developers compared to largely equity financed oil drilling projects.

There is no institition in the USA that is directly comparable to CfDs. However renewable energy developers have to offer cheap prices to sell their energy. This is because of the fiercely competitive nature of US power markets which are dominated by incumbent utilties. These utilities have gotten the expense of the capital costs of their power stations through charging the the consumers - the ratepayers, through their bills.

The utilities build in a profit margin as part of the charges and then bill them again for the energy the power plant generates. There is certainly no room for renewable energy developers to engage in grift. The utilities have creamed that off already!

On the other hand oil and gas projects tend to have much ‘lower gearing’, that is much lower debt to equity ratios compared to most renewable energy projects. A typical oil and gas drilling project will have a debt equity ratio of under 50% (see HERE). But planned returns to equity are much higher compared to bank loans, say 15%. That is justified on the basis that spending on the balnce sheet reduces profits and share values.

This rate of return to equity is much higher than the rate of return needed to repay bank loans. Bank loans will track one percent or so above the ‘base rate’. Base rates are set by the central banks - the European Central Bank (ECB, the Bank of England, the Federal Reserve in the USA etc .

Indeed in the 2014-2022 period European bank loans could be secured by large corporations for next to nothing. This was because the European Central Bank was setting negative interest rates during this period. Of course since then the interest rates sdet by central banks have jumped. This partly explained why renewable energy CfD prices increased.

The overall required internal rate of return (IRR) for a given project will be a mixture of the debt and equity charges. This is weighted according to the debt/equity ratio to produce something known as the ‘weighted average cost of capital’ - WACC. So from this is can be seen that oil drilling involves a much higher rate of return compared to renewable energy investments. This is because the higher the proportion of investment that is derived from equity, the higher the WACC will become. It can also be understood that oil companies may not be so keen on making renewable energy investments if they are going to make less money out of them compared to oil and gas investments!

So oil companies engage in a sort of cyclical activity. Every ten years or so they persuade themselves to show green intentions and proclaim their support for climate initiatives. However then they draw back on them when they realise that, in effect, they cannot soak the consumers as much by investing in renewables compared to oil and gas.

Let’s defend CfDs against the interests of oil companies

Oil and gas companies could potentially make more money out of renewables if CfDs were abolished. Oil and gas companies could get the full wholesale price from the investments, and thus make more profits. Under government-regulated CfDs, which are auctioned off to the lowest bidder, this will not happen. CfDs are the most popular choice among European nations for producring renewable energy projects.

There has been a policy battle over CfDs. Renewable trade associations have been trying to protect CfDs from efforts to end them. Indeed in Germany, The Netherlands and Denmark, the Governments decided to move away from CfDs, They introduced a system whereby developers put in ‘negative bids’, ie pay money to governments, to secure rights to develop offshore wind projects. This has allowed oil interests to outbid mainstream renewable developers for offshore wind licences.

However it is doubtful whether many offshore wind projects will result from this, and if they do, it will be at higher cost to the consumer. Jerome Guillet, who is a leading offshore wind advisor, has made this sort of point arguing that, in effect, oil companies should keep out of renewable energy investments. He backs CfDs as the preferred mechanism. See his blog post HERE

The move towards ‘negative bidding’ for offshore wind licenses has led to furious opposition from renewable energy interests. Both the Euopean Wind Energy Association and a large coalitoon of renewable energy interests are trying to get this polcy revesed and get CfDs reinstated. There has been some success in the case of Denmark, which has now moved back to CfDs. (see HERE and HERE). CfDs remain the most popular means of incentivising offshore wind amongst European countries, including the UK.

Essentially, oil and gas companies should be told ‘hands off renewables'. We should defend the sort of government regulated renewable energy projects that have been organised through CfDs and also feed-in tariffs. CfDs should not be scrapped so that oil companies can make more money out of energy consumers!

Now, if companies want to develop renewable energy projects outside the framework of CfDs, that’s fine. Indeed there may be excellent reasons to do this - eg to sell equity to community owners of solar farms or windfarms. However, this sort of activity should be a supplement to funding renewables through CfDs. CfDs provide a cheap, well regulated means of funding renewables and this process should be enhanced, not watered down or removed.

The high price of oil and gas investments

In Figure 3 I illustrate how much more expensive a typical onshore wind becomes if it is financed under terms used by oil companies as opposed to conventional renewable energy developments. A 2% internal rate of return (IRR) produces the lowest project price for an onshore windfarm at just under £55 per MWh. This may have been possible in about 2018 given negative interest rates set by the European Central Bank.

Today, an IRR of around 6% might be more realistic, and a 6% IRR would give a project cost of around £70 per MWh. But if the project is financed at a higher rate of return, say 12%, then the project cost rises to around £99 per MWh. The 12% IRR is the sort of minimum planned project rate of return (WACC) that would be typical for a an oil company investment. This demonstrates that oil company energy projects will cost a lot more than ones usually organised by the wind industry!

Figure 3

Conclusion

The most important thing is that oil and gas supplies are phased out to save the planet from climate disaster. Oil company advocates claim that such a strategy is expensive. Yet as the evidence in this post shows it is the oil and gas companies with their exploitative relationship with consumers that produce the economic menace that needs to be superceded. Oil companies thrive on the misery of people’s suffering high energy prices during oil and gas price spikes.

The oil and gas companies cannot help themselves but fail to effectively invest in the energy transition. It is the way that their investment portfolios and and practices are structured that produces this outcome i.e. failure to transition to anything that does not involve continued use of hydrocarbons. Investments in renewable energy are regulated through institutions such as contracts for difference (CfDs). Such institutions do not allow developers to make super-profits comparable to the incredible billions earned by the oil and gas companies every year.

By contrast the system over which the oil and gas companies preside plunges the world into regular economic crises - and profits from it at the same time in a way that pays no heed to the policies of governments or the needs of its peoples. Meanwhile an alternative system based on energy efficiency and renewables is supressed by the oil industry’s investment patterns. These demand massive profit levels.

Renewable energy, as regulated by governments (involving CfDs), provides security, consistency and much less economic risk compared to oil and gas. Renewable energy can help save the planet from the climate crisis. The oil companies, by contrast, thrive on environemntal destruction.

This piece clearly exposes the core issue: oil and gas companies are not just failing to transition; they are structurally incapable of doing so under their current profit-driven model.

The fact that renewable energy (economically stable and environmentally safer) does not allow for “super-profits” is exactly why oil giants are not interested. Their profit depends on volatile markets, consumer exploitation, and environmental degradation, not stability or sustainability.

Sustainability is not their favourite word and quite frankly not a concern to them.

It is sobering to think that in the early industrial age, energy was seen as a public good which was meant to power society, not punish it. Public utilities, cooperatives, and even early oil discoveries were treated with the belief that energy should uplift nations. As meant to be. But as corporations took control, the mission shifted from service to shareholders. What started as a tool for development became a mechanism for dominance. For power.

I think it is time we stop expecting oil companies to lead a transition that they are financially incentivized to avoid. Yes, avoid. Instead, governments and communities must shift resources and policies to scale renewables, enforce transparency, and break the toxic dependency on hydrocarbons.

In places like Africa, this shift has come at a huge cost: despite being rich in resources, many communities still live in energy poverty, while oil wealth fuels inequality, corruption, and environmental degradation. Growing up around this, I’ve seen how oil can build shiny cities for the few while leaving entire regions in darkness.

The future belongs to systems designed for people and planet, not for quarterly profit margins.

Energy justice (if we can say it this way) must be more than a slogan. It must be the new system we build.