In the UK it has almost become an accepted truth in the media that new nuclear power is needed because there is no other practical or cheaper way to balance fluctuating wind and solar power. Yet not only is this demonstrably false, but it actually runs counter to the way that the UK electricity grid is going to be balanced anyway. Essentially the UK’s increasingly wind and solar dominated grid is going to be balanced by gas engines and turbines that are hardly ever used. But you would never guess this from the coverage.

Usually the line goes that on windless and sunny days nuclear power is needed to balance wind and solar. But the truth is that adding Sizewell C will not help solve the problem - not even bankrupting the country with several more nuclear power stations will help solve this problem. Instead, we need a system where a) renewables generate the energy, b) batteries help smooth the system and where c) gas turbines or engines provide capacity rather than generate much energy.

Nuclear power (even with Sizewell C and the odd so-called ‘small’ modular reactor) do not add up to more than about 15 per cent of peak demand. So where is the rest of the balancing coming from? The answer of course is gas fired power plant, which will needed for increasingly small periods of time as solar, wind and ever cheaper batteries build up. That’s the way the UK’s clean power plan will work in practice. The extra nuclear plant are, in effect, a bit of enormously expensive window dressing.

Sadly, this point is not well understood. This is because there is little understanding of the difference in the role of gas plant between a) providing capacity and b) its role in providing electricity. We are going to need gas plant capacity, but only if the gas plant actually produce electricity for as little time as possible. More and more batteries will make this easier and cheaper. See my post HERE discussing this.

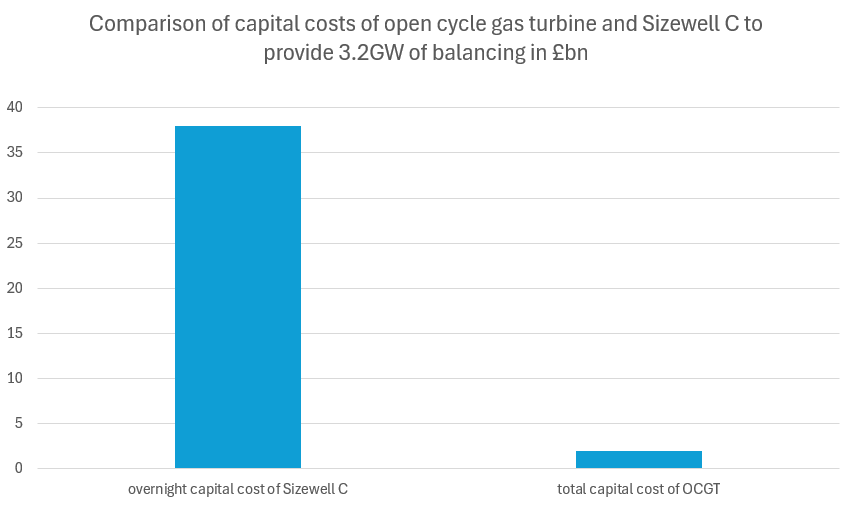

The Government’s clean power plan (see HERE) suggests that no more than 5 per cent of power supplies will be needed to be supplied by gas. This is as the Government’s renewable energy buildout achieves its objectives - by 2030 (or maybe a bit later!). In other words we shall have a lot of gas power plant on standby that will hardly be ever used. But that is not a problem because simple gas fired power plant are many times cheaper per MW compared to nuclear power plant. This is demonstrated by Figure 1.

This Figure 1 compares a) the £38 billion estimated cost of building the 3.2 GW Sizewell plant in terms of co-called ‘overnight’ costs (ie without adding interest charges) (see HERE) with b) a cost for building the same capacity of gas fired power plant open cycle gas turbines (OCGT). OCGT costs are assumed to be around £600,000 (£0.6 million) per MW which means around £1.9 billion for 3.2 GW of capacity. The cost comparison illustrates the fact that in order to balance fluctuating renewable energy plant we need more flexible standby gas plant, not more nuclear power.

Figure 1

Costs and benefits of more nuclear power

There is no doubt here that building more nuclear power is an immense waste of money. The comparison in Figure 1 implies that the UK taxpayers and electricity consumers will lose most of the £38 billion spent on Sizewell C (which will be a lot more in practice as interest payments and almost certanly cost overruns are added). Indeed the Treasury has already spent or committed, by 2030, over £17billion of taxpayers money to be spent on Sizewell C without any chance of the scheme generating electricity until after 2040.

It is not as if the extra nuclear plant will actually take us much closer to eliminating gas power completely. You can see this from the case of France, where they now generate around two-thirds of their electricity from nuclear power with the rest coming from renewables, waste-to energy plant, and fossil fuels. Yet even in France, in 2024, there are still residual amounts generated from fossil fuels even with the very large proportion of power coming from nuclear power. In 2024 just under 4 per cent of total electricity was generated from fossil fuels, mainly gas.

Are there any benefits? Well, the nuclear power industry gains, obviously. But the running costs of the system are not going to be lower. That is because the operating costs of a given capacity of nuclear power plant are not going to be lower than the equivalent capacity of gas-fired plant. It is the energy burning that makes gas power expensive, and the gas fired power plant will be burning very little of that. All that will be left will be maintenance and insurance costs for the gas plant. Nuclear power plant are rather more complicated institutions that also include fuel costs.

But how much gas will be saved with the extra nuclear power plant? Probably not very much. If, under the Government’s clean power plan gas will still be responsible for doing most of the balancing. They will only be producing 5 per cent of the electricity. But how much difference will adding Sizewell C make? This adds a further 7 per cent of generation of energy production on top of the other 15 per cent or so nuclear biomass and hydro production (generally called ‘firm’ capacity) currently in operation. However Sizewell C will make little impression on windless days compared to the gas fired power plant.

Maybe Sizewell C might save a bit of gas, lets say, to be charitable, 0.5 per cent out of the 5 per cent of annual gas generation that will remain (compared to alternative wind or solar PV). This would save around £200 million a year in avoided gas costs at current prices - that is if it were not for other factors. This is not much of an annual return on over £40 billion.

However there are also costs to the system of operating inflexible nuclear power plant which reduce or completely negate even these savings. This is because of the way British nuclear power plant are being contracted (eg the Hinkley C contract). They are encouraged to run all of the time. This means that they will displace a lot of renewable energy, thus wasting the value of that generation. So maybe the new nuclear power will not save any money from running costs at all! It may be argued that a solution is to make new nuclear power plant ‘load follow’. However this will not be accepted by new nuclear’s investors (basically the Government and EDF) since it will reduce the already miserable project returns to nothing.

Apart from that, new nuclear power is a much more costly option compared to renewables when energy production is concerned, as can be seen in Figure 2. This compares prices of contracts-for-difference issued for onshore and offshore wind and solar PV farms. The figure shown here for Hinkley C (the £92.50 for 35 years contract expressed in 2024 prices) is likely a big underestimate. This because EDF (or rather the French taxpayer since EDF is state-owned) has been paying for large cost overruns in building the project.

Figure 2

The most flexible generators around are open cycle gas fired plant (OCGTs) and gas engines, to be distinguished from combined cycle gas turbines - CCGTs - which are less flexible. CCGTs are built to maximise electricity production, not to provide capacity as such. We do not need any more CCGTs, but we do need more simple gas turbines and gas engines to provide capacity in the times when there is not enough wind or sun.

In terms of eliminating the carbon emissions, the 40 billion would get much higher returns on energy efficiency. For example, setting up a scheme to pay £15000 each to 500,000 residents not on the gas grid to switch to heat pumps will likely save as much carbon as Sizewell C is likely to save. The residents will be switching from oil fired and gas bottle fired heating. Doing this will cost rather less than a fifth of the cost of Sizewell C. There are various other possibilities to spend the money better as well to reduce carbon emissions.

But then, for many of nuclear power supporters, building new nuclear power is not really seen as being about cutting carbon emissions. Otherwise Nigel Farage would not be in favour of it! Nuclear power appeals to a sort of militaristic approach to energy policy. But military defence and war is not at all the same as producing affordable sustainable energy.

Getting rid of all carbon emissions from electricity, heat and transport

Getting rid of the last 5 per cent of non-fossil electricity generation is the most difficult. But doing it through nuclear power is unachievable. We would need something like green hydrogen, produced from renewable energy, and kept in storage. I wrote a blog post about this HERE.

There are other possible solutions, and no doubt they will develop as technology progresses. But of course, apart from putting together demonstration schemes, we do not need to do this in the next few years. What we do need to do now is, as well as rapidly expanding renewable energy, is to expand electrification into the low hanging fruit of decarbonisation. That means, as first stops, electrifying heat and transport. Building more nuclear power plant merely wastes the meagre funds that are being currently spent on decarbonisation.

A simple way to see it is that you can't provide temporary supply with a plant that's meant to be running all the time... It will already be running (or be unable to run for unrelated technical reasons)

Electricity to consumers in the UK are inordinately high in part because the highest marginal cost wholesale pricing mechanism is dominated by gas. Taking gas pricing into a new “out-of-market” mechanism would serve two vital purposes. First it could and should anticipate paying for the use of gas to provide capacity and not MWs. Second it would immediately cause the price of electricity to better reflect the cost of renewables, reducing electricity prices to domestic and business users alike. This would make not just economic sense, but political sense by demonstrating that decarbonising the electricity supply is a benefit today, not just jam tomorrow.